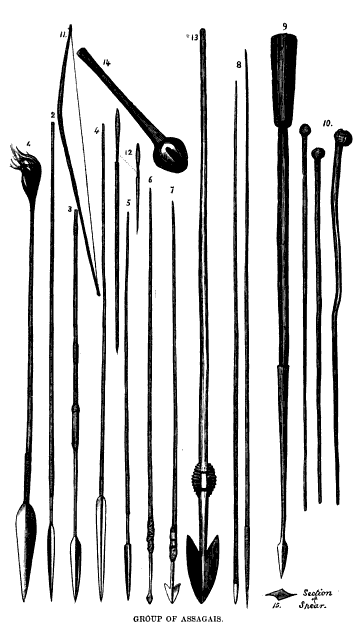

As part of the “Losses Project”, employees of the Malbork Castle Museum study an unusual document. It is the so-called Blell’s inventory, i.e. a list of the collection of Theodor Joseph Blell, a 19th-century Prussian collector, whose collections became the basis of the no longer existing, pre-war military collection of the Malbork castle. Among the hundreds of objects belonging to both the military and historical and ethnographic categories, the Inventory mentions special monuments, some of which we would like to gradually present here. At the beginning, we will deal not so much with the peculiar object as with its rather unusual description. Here, among the weapons classified as African, the Inventory mentions: 1 Kafra javelin (sagaj) with the ending as the son of Napoleon III. This laconic description, although relatively extensive compared to many others included in the Inventory, contains not only information about the object in the collector’s collection, but also echoes the event that was a sensation and the subject of general interest at the end of the 19th century.

In 1852, the nephew of the Emperor of the French Napoleon I, Charles Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, attempted to renew his uncle’s French empire, declaring himself Emperor of the French following his example “by the grace of God and the will of the people.” The empire of the new emperor Napoleon III, turned out to be almost twice as durable as the imitated original, but it was ended by the lost Franco-Prussian war of 1870-1871. Dethroned Napoleon III moved to England, where he died after just two years at the age of 65.

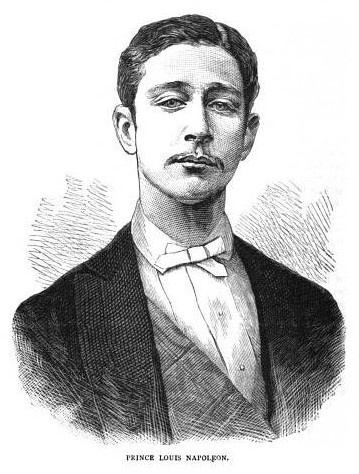

Soon after the proclamation of the Second Empire, Napoleon III was born as the only righteous descendant, named Napoleon Louis Eugene (and several others), and who became the main character of the drama indirectly recorded in the above-cited entry in the Blell’s Inventory.

Napoleon Louis Eugene Bonaparte, called by his relatives Loulou, at the age of 14 survived the end of the empire, in which he succeeded to the throne, to find a new home in Great Britain with his parents – the dethroned imperial couple. After his father’s death in 1873, he was proclaimed another emperor by the Bonapartists – Napoleon IV, but this proclamation had no practical significance. The young titular emperor of the French, still as the heir to the throne, started his education in England, graduating with a very good result from the Royal Military Academy and then serving for some time in British artillery.

The problems of the Third Republic in France gave the supporters of the Empire an illusion of a change of fate and the titular emperor living in the Islands remained the embodiment of their hopes. However, the latter leaned more towards the war than politics. Perhaps soberly assessing his chances as an exiled emperor, he saw a future in a military career, or perhaps the blood of Bonaparte was just boiling in the young man. When the Zulu War broke out in 1879, he forced the British authorities to agree to his participation in military operations in southern Africa using all possible means.

And so the 23-year-old Lieutenant Bonaparte, entrusted to the care of experienced British commanders, began to fulfill his dreams of participating in a real war. Apparently, he took with him the sword of his great namesake, which he used at Austerlitz. Everything he did was filled with enthusiasm, proving that he finally felt like the right person in the right place. All the time remaining under strong escort, he did not receive dangerous tasks, but the war to which he struggled so much did not prove to be kind to him.

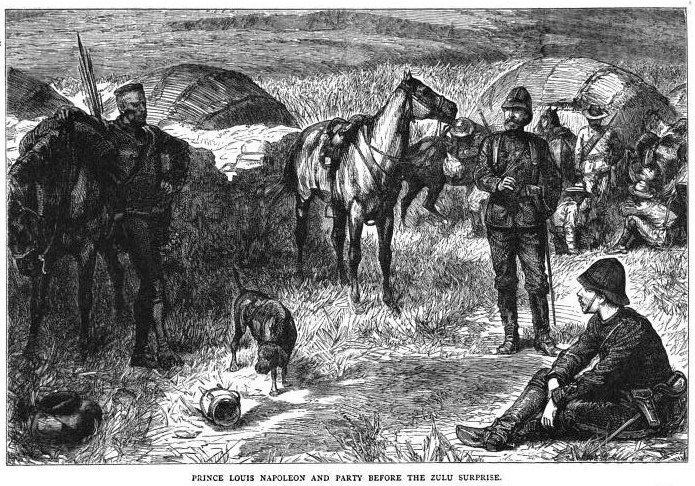

On June 1st 1879, a small detachment actually commanded by Bonaparte set out for reconnaissance, which was agreed by the British commander, being convinced that there were no enemy troops in the patrolled area. It was soon proved how wrong he was, when the English led by the French were attacked by about 40 Zulus. Young Bonaparte fought bravely, but the successive wounds inflicted on him efficiently with Zulu javelins deprived him of the strength to defend himself. Some of his squad died, some saved their lives by escaping. 18 wounds inflicted with a Zulu javelin known as assagai were found on the body of the untimely chief of the patrol, found the next day. The news of the death of a pretender to the imperial throne spread like wildfire around the world, already then equipped with quite efficient and invariably sensationalist media. The events in the South African savannah were talked about everywhere and, as is usually the case in similar situations, it was discussed who was to blame and who benefited from Bonaparte’s death. Both the French republicans and the British and even Freemasons, were accused.

However, for our Inventory, more important than the question of guilt or only responsibility for the unfortunate fate of “Napoleon IV”, is that the whole world also heard the name of the weapon that ended his young life. Assagai, known in Polish as sagai, which is the simplest possible version of a polearm with a short wooden shaft and an iron spearhead, has become a well-known concept. And that is why the author of the Inventory, instead of trying to describe the not very characteristic shape of the African spearhead, limited himself to information about its similarity or even identity with the one “who pierced the son of Napoleon III”. The quality of this information leaves much to be desired, because what significantly distinguished the individual sagaya pieces was the shape and size of the spearhead.

Such a description of an object is an example of a highly simplified and imprecise method of showing the features of items placed in it that runs through the entire Inventory. At the same time, it reflects the state of knowledge of people involved in the creation of the Inventory and also perfectly illustrates the danger of using in similar descriptions a context well known and understood at the time of its use, in many cases completely forgotten and illegible after several decades.

For the sake of order, it should be explained that the Kafras mentioned in the entry in the Inventory are the former name of Bantu – a group of about 400 peoples of the southern part of Africa, including Zulu.

(compiled by A. Masłowski)